At OFC 2019 in San Diego we posed the question how a practical integration of quantum channels into passive optical access networks could look like. To do so, we should first pay attention to the FSAN roadmap. 5G is on the brink of being rolled out together with its optical fronthauling over cloud-radio limited reach of ~20 km, while access standards incorporate wavelength stacking towards 4 lanes of 10 Gb/s. The good news is: NG-PON2 with its WDM overlay is spectrally allocated at the C- and L-bands. This blanks out the O-band, and if we expect fiber deployment to dismiss legacy solutions, there is really much unoccupied space down there at 1310 nm.

Although quantum communication is not a resource-consuming technology with respect to the always precious optical spectrum, it is very picky when it comes to “contamination”. The high power difference of about 100 dB between classical and quantum channels can quickly become a showstopper when these channels are located too close to each other. Even the 100-nm far wings of stimulated Raman scattering are quickly imposing severe crosstalk to the quantum channel. Spectral displacement is therefore paramount, and the consolidation of down- and upstream channels of the next-generation PON standard in the C/L-band definitely helps.

The second big question concerns the loss budget. In optical telecommunications the signal-to-noise ratio worsens with an increasing loss introduced between transmitter and receiver. In the quantum world, however, we transmit single photons and loss is directly impacting the rate at which we are receiving them. Given the constant dark count rate of single-photon detectors, there is a hard limit at which no useful quantum signal can be received anymore. Unfortunately, PONs as the scene that we have set for our experimental deployment study, are known to be very lossy due to their broadcast-and-select methodology with concentrated 1:N branching loss. At ECOC’14 in sunny Cannes, Orange gave a hint on that loss figure by showing that their average optical budget in access networks is 22 dB. This is a good indicator for brown-field deployments and it is just compatible with GHz-rate quantum signals.

So, what is left is to put all together, and that’s what we show in our OFC paper. We exploit a conceptually simple laser-based quantum transmitter dedicated to the end-user premises. The complexity of the receiver, with its custom quantum detector, is centralised at the head-end where it can be cost-shared. With that, and by exploiting a dual-feeder scheme for the PON as well as the unidirectional nature of quantum channels, we obtain robustness to a high number of more than 50 downstream channels. However, we also notice that classical upstream channels are by far more detrimental for our fragile quantum signal. Emerging WDM standards in the O-band, such as LAN-WDM with smaller channel passbands than CWDM, promise a much better noise rejection feature – and after all, you can also include a custom narrowband filter if you already require an equally complex element such as a quantum receiver. For these reasons, we believe that 1310 nm is an attractive wavelength to dress our quantum channel.

See our technical paper for more information:

B. Schrenk, M. Hentschel, and H. Hübel, “O-Band Differential Phase-Shift Quantum Key Distribution in 52-Channel C/L-Band Loaded Passive Optical Network,” in Proc. OFC’19, San Diego, USA, Mar. 2019, Th1J.5.

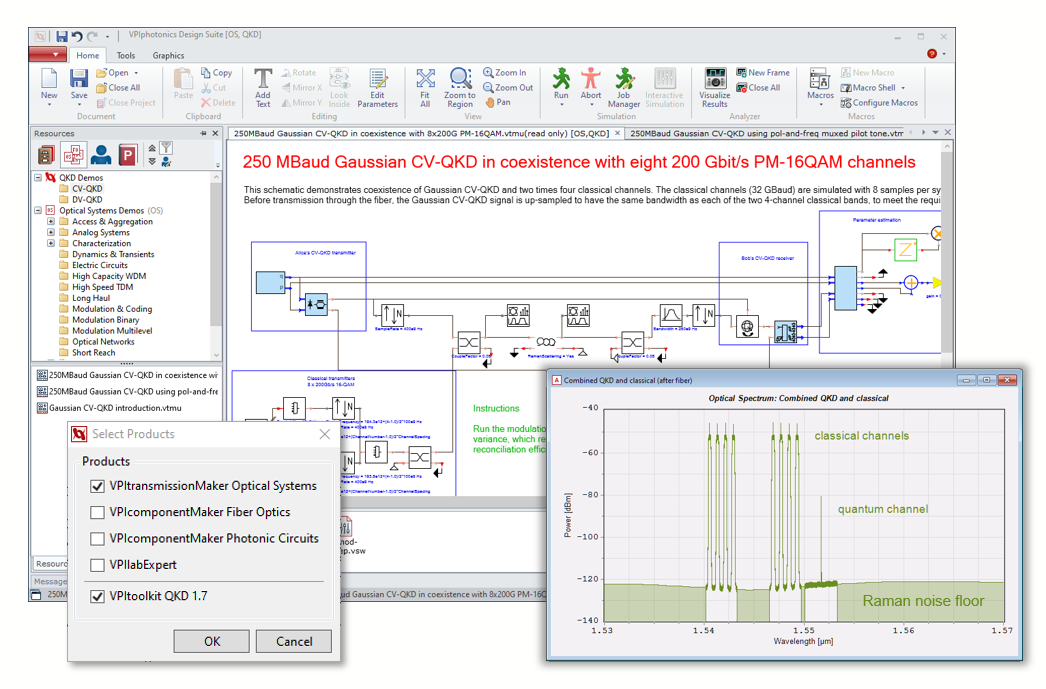

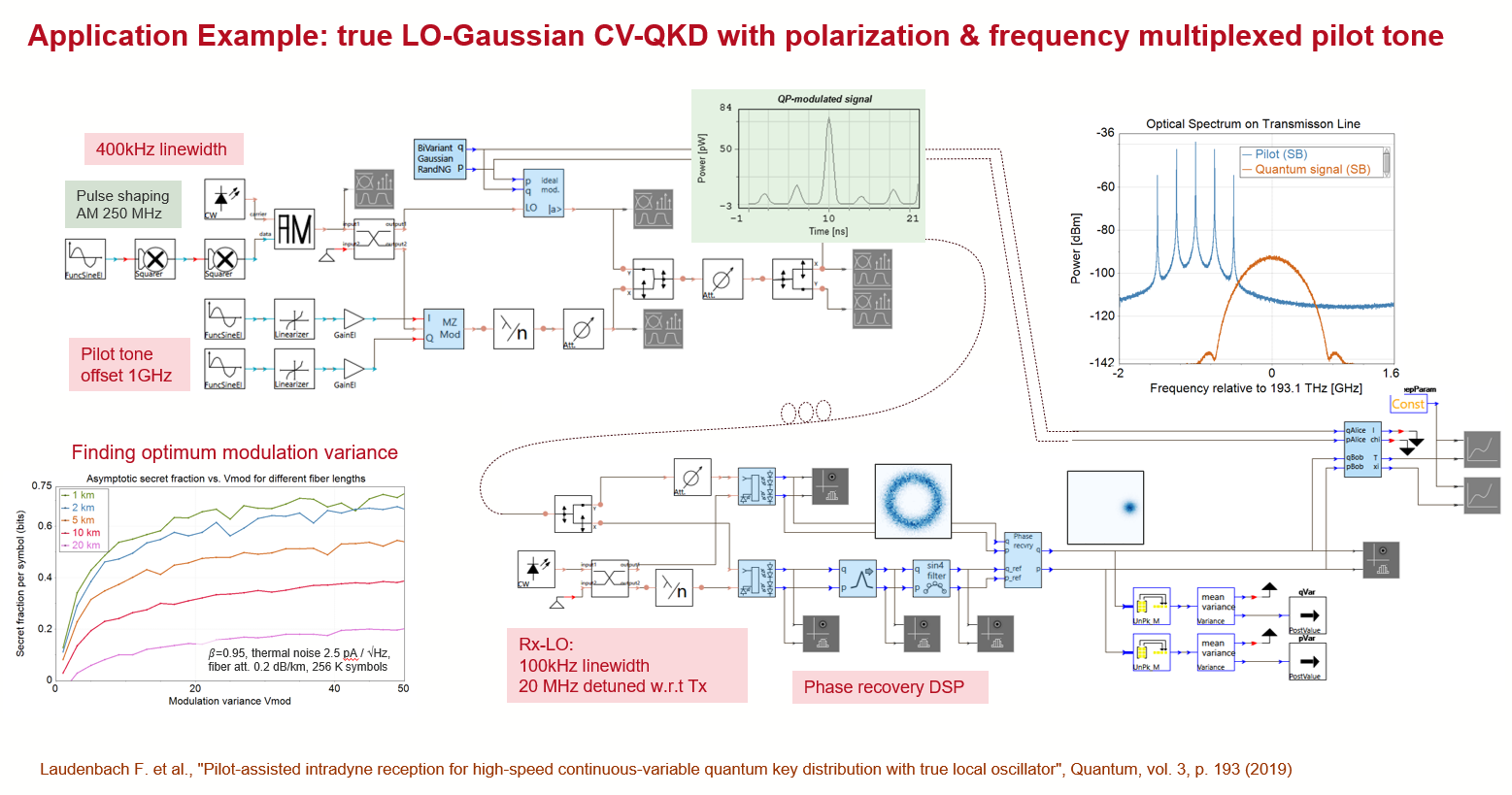

VPIphotonics announces a new release of its simulation and design tools VPIphotonics Design Suite™ 11.1 and VPItoolkit™ QKD 1.7. When used together, they represent a powerful R&D environment for the development of QKD systems based on weak-coherent prepare-and-measure protocols, including co-existence scenarios with classical channels. VPItoolkit™ QKD provides modules for both CV- and DV-QKD including transmitters and receivers, parameter estimation, and secret key rate calculation. The design environment can serve as a test bed for the development and evaluation of various implementation options of QKD systems and sub-systems, such as pulse shaping, signal recovery and filtering, and others. The toolkit offers capabilities for modeling a wide range of component imperfections by inheriting the versatile numerical approach of VPItransmissionMaker™ Optical Systems (part of VPIphotonics Design Suite™), including thermal noise, ADC quantization noise, RIN, phase noise, dark count rates, afterpulsing, dead time, etc. Also, exploiting the powerful model libraries coming with VPItransmissionMaker™ Optical Systems, the toolkit allows to investigate various deteriorate effects such as Raman scattering and cross-talk from classical channels in co-existence scenarios. The in-build sweep and scripting functionality offers a convenient way to optimize simulation parameters such as modulation amplitude, photons per pulse, filter bandwidth, BB84 basis probability, symbol rate, and others. In summary, VPIphotonics Design Suite™ and VPItoolkit™ QKD are valuable design and optimization tools for researchers and engineers working in the area of quantum communications. The foundations for VPItoolkit™ QKD 1.7 have been laid in the Quantum Flagship project UNIQORN.

VPIphotonics announces a new release of its simulation and design tools VPIphotonics Design Suite™ 11.1 and VPItoolkit™ QKD 1.7. When used together, they represent a powerful R&D environment for the development of QKD systems based on weak-coherent prepare-and-measure protocols, including co-existence scenarios with classical channels. VPItoolkit™ QKD provides modules for both CV- and DV-QKD including transmitters and receivers, parameter estimation, and secret key rate calculation. The design environment can serve as a test bed for the development and evaluation of various implementation options of QKD systems and sub-systems, such as pulse shaping, signal recovery and filtering, and others. The toolkit offers capabilities for modeling a wide range of component imperfections by inheriting the versatile numerical approach of VPItransmissionMaker™ Optical Systems (part of VPIphotonics Design Suite™), including thermal noise, ADC quantization noise, RIN, phase noise, dark count rates, afterpulsing, dead time, etc. Also, exploiting the powerful model libraries coming with VPItransmissionMaker™ Optical Systems, the toolkit allows to investigate various deteriorate effects such as Raman scattering and cross-talk from classical channels in co-existence scenarios. The in-build sweep and scripting functionality offers a convenient way to optimize simulation parameters such as modulation amplitude, photons per pulse, filter bandwidth, BB84 basis probability, symbol rate, and others. In summary, VPIphotonics Design Suite™ and VPItoolkit™ QKD are valuable design and optimization tools for researchers and engineers working in the area of quantum communications. The foundations for VPItoolkit™ QKD 1.7 have been laid in the Quantum Flagship project UNIQORN. Image source: Quantum Flagship

Image source: Quantum Flagship

Our project coordinator Hannes Hübel will be speaking at the 2nd edition of Quantum.Tech, which is being held at Twickenham Stadium, London, 20-22 April 2020.

Our project coordinator Hannes Hübel will be speaking at the 2nd edition of Quantum.Tech, which is being held at Twickenham Stadium, London, 20-22 April 2020.